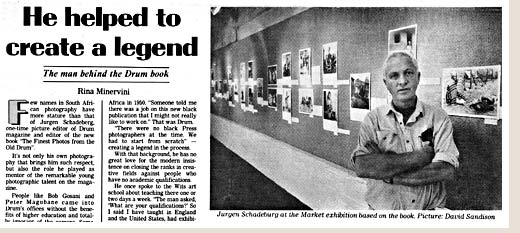

He helped to create a legend

The man behind the Drum book – By Rina Minervini

Few names in South African photography have more stature than that of Jurgen Schadeberg, one –time picture editor of Drum magazine and editor of the new book “The Finest Photos from the Old Drum”.

It’s not only his own photography that brings him such respect, but also the role he played as mentor of the remarkable young photographic talent on the magazine.

People like Bob Gosani and Peter Magubane came into Drum’s offices without the benefits of higher education and totally ignorant of the camera. Some of the results of Jurgen’s teaching can be seen in the book.

He can’t explain why these men –the first black photographers in South African journalism - developed so quickly. “I have taught highly educated students in England and New York who still don’t get anywhere in three years. Bob Gosani was 17 (Jurgen himself was only 20 when he started working at Drum) and within a year and a half he took some brilliant pictures.

“It might be that there was this opportunity, there was no competition. A similar thing happened in television in the United Kingdom in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s. Later it became too professional.”

Jurgen, who studied photography as a 16-year old in Germany and then worked for a Hamburg Press agency, emigrated to South Africa in 1950. “Someone told me there was a job on this new black publication that I might not really like to work on.”

“There were no Black Press photographers at the time. We had to start from scratch” – creating a legend in the process.

With that background, he has no great love for modern insistence on closing the ranks in creative fields against people who have no academic qualifications.

He once spoke to the Wits art school about teaching there one or two days a week. “The man asked, “What are your qualifications?” So I said I have taught in England and the United States, had exhibitions, published several books…’No, I don’t mean that. What degrees do you have?”

“I have twice met people in England who were born actors, and although their life’s ambition was to be actors, both of them did something very mundane simply because they didn’t get into Rada. I argued with them, asked why didn’t they start shifting scenery or looking after props, but they thought they had to have the qualification.

“I think it’s become like that over the whole world because of overpopulation. The people at the top defend themselves with walls and degrees.”

Formal training in photography has proliferated recently because of its importance in all kinds of fields, from police work to anthropology. Not only must people know how to make photographs, they must know how to read them, too. Jurgen finds the differences between cultures in this aspect interesting.

“If you show a photograph to an unsophisticated black person they spend a long time on it, and look at every little bit in that picture. I knew some people who went around in Africa showing instruction films to peasants in villages. In one village everybody was talking about a chicken in one film. The people showing the film hadn’t seen a chicken at all. Eventually they found it,, on two or three frames a chicken ran in and out of the corner of the picture.”

White South Africans, in contrast, seem to be influenced by word-oriented English culture.

“In England there is a very high standard of writing, but visually they’re clumsy. The average art college student of between 18 and 20 would have a visual education about as high as the average 10-year-old in Italy or France.”

Moreover, the way in which pictures are perceived in any culture will differ from time to time. An Italian magazine once did a study in which the full contact sheets from which famous photographs like Robert Caa’s dying Spanish Civil War soldier were taken. The selection of the one to print was as much a product of the time as of the worth of the picture. (The Capa Soldier, incidentally, was not dying at all, says Jurgen. Alater photograph in the series shows him alive and well.)

The Drum pictures would probably not, for instance, have been printed then in the same way as they appear in the book. Details now seen as meaningful would then have been cropped off.

In any case, the excitement in this collection derives from the fact that the photographers were not trying to create works of art: they were concentrating on being journalists and recording their society.

“These pictures are very ordinary,” says Jurgen. “They tell life as it really was. They’re all moments, attempts to produce one picture that at least to the photographer represents the completeness of that person in that environment. To get that right is a very rare thing. When it happens, then it’s magic.”